Ferdinando I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1548-1609) was the son of Cosimo I de’ Medici and Eleanora de’ Medici.

His future career seemed uncertain until, in 1562, two of his brothers and his mother suddenly died (he was the fourth son).

The older of the two, Giovanni, had been a cardinal; Cosimo arranged with Pius IV that Ferdinando should inherit Giovanni’s title and benefices in 1563.

The investiture took place in Rome the following year.

For the next decade Ferdinando spent increasingly long periods in Rome, lodging frequently with the Tuscan cardinal Giovanni Ricci, and made numerous influential contacts and alliances. He also began, from 1569, to collect antique sculptures, housing them in a small villa outside the Porta del Popolo.

In 1572 Cosimo commissioned Bartolomeo Ammannati to remodel and enlarge considerably the Palazzo di Firenze in Campo Marzio, Rome, as Ferdinando’s main residence, but little work was done before Cosimo’s death (1574) put paid to the scheme. Nevertheless Ferdinando was determined to move permanently to Rome because his relations with his elder brothe Francesco I de’ Medici were strained.

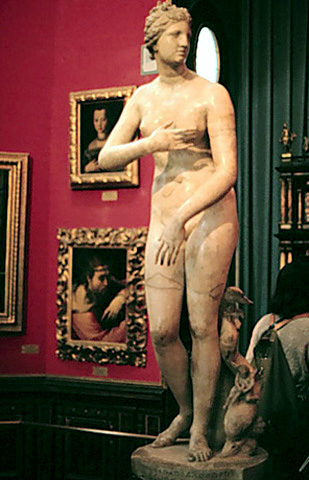

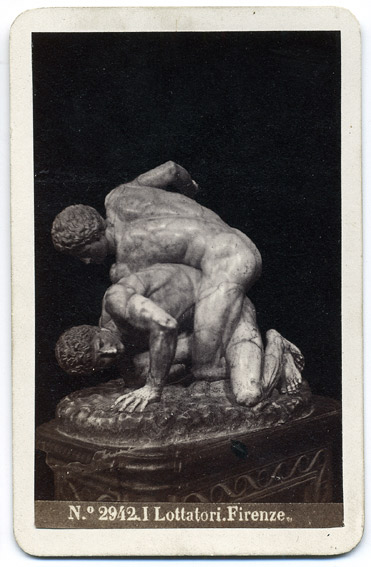

In 1576 he completed the purchase of Cardinal Ricci’s magnificent villa on the Pincio, which is still known as the Villa Medici. Over the next decade it was rendered even more splendid, with the approaches and entrances regularized and embellished, the gardens enlarged and transformed, and the main building remodeled and redecorated. Two of the new architectural features were especially influential on subsequent Roman villas and palazzi: the crowning of the doubled turrets with decorative belvederes, and the encrustation of the garden front, above a deep loggia, with antique fragments framed in rich stuccowork. The other main new feature was an immense gallery below a raised terrace, built to house Ferdinando’s superb collection of Classical sculpture, which eventually included the Venus de’ Medici, the Wrestlers, the Niobids and the Spinario.

Ferdinando’s fine physical presence, good humor and liberality made him popular both in Florence and Rome; but it was clear from the decisive influence of his intervention in the papal conclaves of 1572 and 1585 that his fellow cardinals recognized more solid qualities beneath his affable exterior. The Florentines too were to discover that he could be both decisive and ruthless. In 1582 Francesco’s only legitimate son had died; the son of Francesco’s second wife, Bianca Capello, was then legitimized. When both Francesco and Bianca died suddenly in 1587, Ferdinando quickly found witnesses to swear that the boy was not, in fact, Francesco’s son and soon entered him, for good measure, in the celibate Order of the Knights of San Stefano. Ferdinando himself had never taken priestly vows and was thus able, with Pope Sixtus V’s permission, to discard his cardinalate (which was conferred on Francesco Maria del Monte) and become Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Ferdinando’s coup was popular with his new subjects, who had come increasingly to detest his brother. He proved an able administrator and with firmness and efficiency secured for Tuscany stability and prosperity at home and independence and respect abroad.

He spent as lavishly as Francesco had, but was less resented for it, perhaps because his projects tended to be of a more public and lasting nature and many more of them were brought to completion.

In fact, several were based on his brother’s initiatives. He regularized the haphazard grouping of craft workshops in the Casino de’ Medici by transferring them, together with painters’ studios, to the newly completed Uffizi, under the supervision of a single Soprintendente.

In 1588 he founded a workshop, later known as the Opificio di Pietre Dure, for the control and encouragement of workers in hardstones. He had Bernardo Buontalenti execute the planned Forte di Belvedere above the Boboli Gardens, and in 1596 he held a second competition for the façade of Florence Cathedral. This was won by his half-brother Giovanni de’ Medici; work was eventually begun to the latter’s design, but soon abandoned.

Above all, Ferdinando continued his predecessor’s development of the port of Livorno from virtually nothing into an international trading center. Even more important was the city’s internal rearrangement: in 1594 Francesco had begun the rebuilding of the cathedral by Alessandro Pieroni to Buontalenti’s design; but it was under Ferdinando that the symmetrical Piazza Grande in front of it was laid out, with mixed commercial and residential properties encased in a consistent architectural configuration. This was soon imitated by Ferdinando’s nephew-in-law, Henry IV, King of France, in the Place Royale (now Place des Vosges), Paris, and subsequently by Inigo Jones at Covent Garden, London (1631), both with dramatic effect on European urban planning.

Livorno also contained another influential feature, an over life-size marble statue of Ferdinando by Giovanni Bandini in the Piazza Micheli, overlooking the port. Inspired by his love of the Antique and knowledge of Roman monuments, Ferdinando replaced painting with sculpture as the dynastic image-maker. Two other large statues of himself, by Pietro Francavilla to Giambologna’s designs, had been set up in Arezzo and Pisa.

The latter accompanied a similar figure of Cosimo I by the same artists, surmounting a fountain before the Palazzo dei Cavalieri. Cosimo had been even more influentially immortalized by his son in Giambologna’s superb bronze equestrian statue in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. Ferdinando was portrayed in similar guise, the metal supposedly from Turkish arms captured by his victorious fleet. While Giambologna was working on the latter (completed by Pietro Tacca), he was commissioned to produce comparable statues of Henry IV and Philip III. These conquering images were to become a staple of Baroque portraiture.

Ferdinando sat for only one official portrait painting, by Scipione Pulzone, a pair with that of his wife. He had married Christine of Lorraine (Catherine de’ Medici’s granddaughter) in 1589, with festivities more lavish than any before, including processions, masques, theatrical intermezzi and a mock sea battle in the flooded courtyard of Palazzo Pitti. Equally lavish, though more sober, ceremonies marked the obsequies of Philip II (1598) and the marriage of Marie de’ Medici and Henry IV (1600).

Most splendid of all were those celebrating the wedding (1608) of Ferdinando’s son Cosimo II de’ Medici to Maria Maddalena of Austria, which culminated in a mock battle on the Arno between numerous fancifully decorated ships. The true splendor of the Medici, however, was expressed in the Cappella dei Principi at San Lorenzo, a huge octagonal mausoleum in which the tombs of the Grand Dukes were to be preserved in the gloomy opulence of imperishable pietre dure.